Jesters

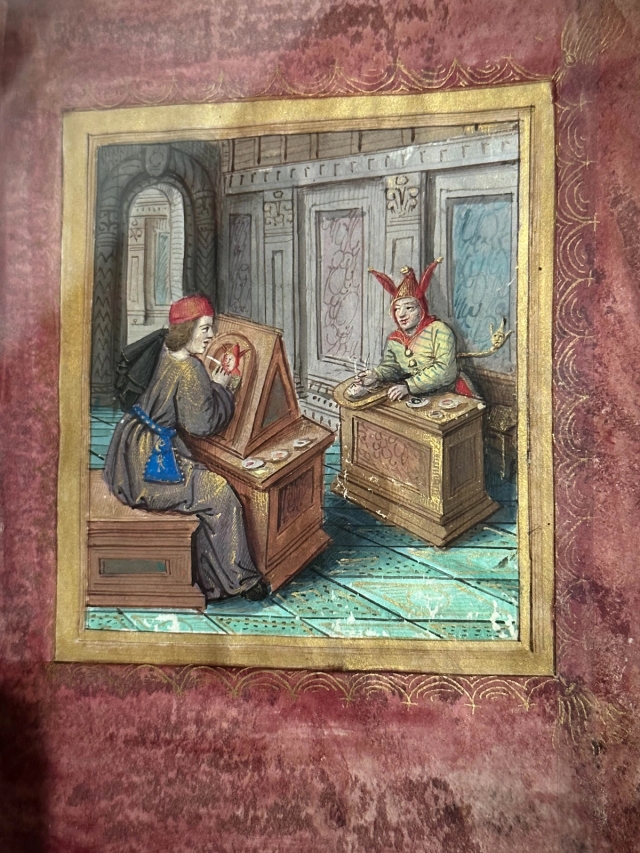

Jean Perréal (about 1455-about 1530)

A man painting a portrait of a jester (the Wise Man and the Fool)

Illumination on parchment

This Petit Livre d'Amour (Little Book of Love) was produced by the humanist (man of letters) Pierre Sala (about 1457-1529) for his betrothed. Its poems deal mostly with love, but also morality. Here, a wise man of letters, depicted as an evangelist at his lectern, and a fool are drawing each other, illustrating the maxim on the left-hand page that denounces the world's hypocrisy, which makes the wise man play the fool and vice versa.

We take the times as worldly school

To play our parts, the times advise

The wise man counterfeit the fool

The fool pretend that he is wise.

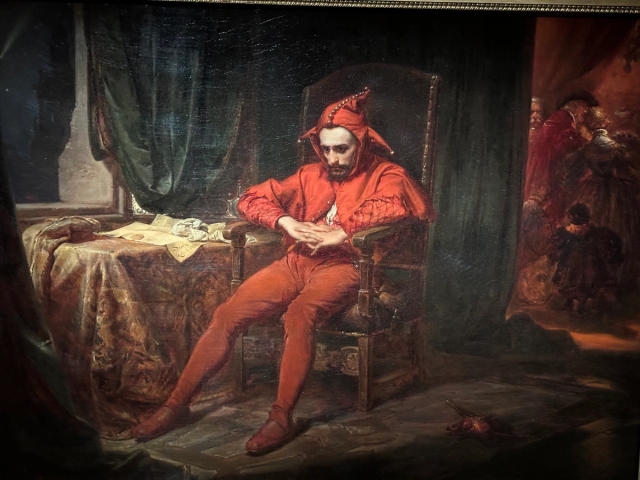

Jan Matejko (1838-1893)

Stanczyk at a Ball at the Court of Queen Bona after the Loss of Smolensk

Oil on canvas

Poland

This painting shows Stanczyk, jester at the Polish court, grieving the loss of Smolensk, a city taken by the Russians in 1514. He stares stricken at a letter announcing the defeat. In the background, a royal ball symbolises the contrast between the court's frivolity and the jester's political awareness. The painting reflects the artist's concern for his country, on the brink of the January Uprising of early 1863.

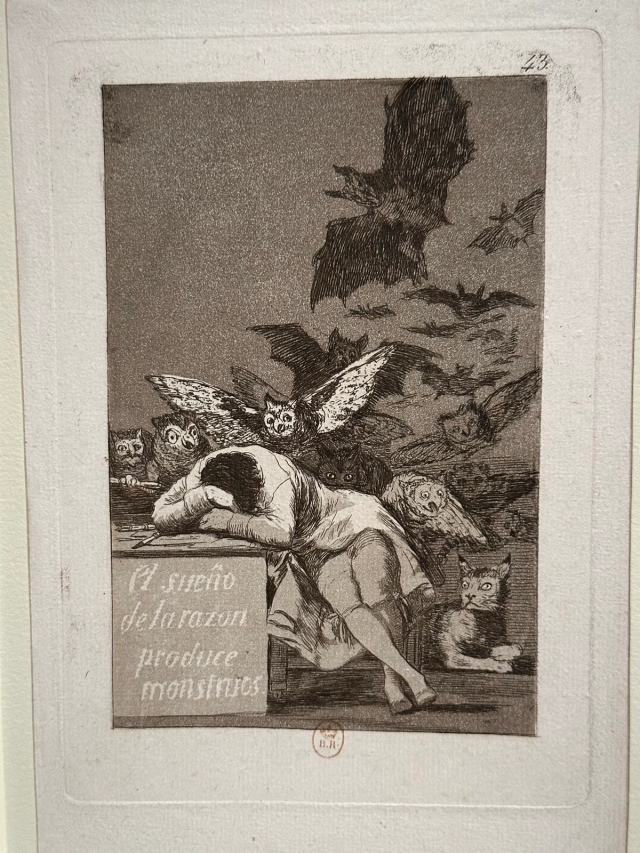

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes

El sueño de la razón produce monstruos (The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters)

Plate 43 of Los caprichos

Spain, 1799

Etching, aquatint

The Tempter and A Foolish Virgin

Cast of statue from the portal of Strasbourg

Cathedral - from original work in sandstone, late 13th century

These statues, The Tempter and A Foolish Virgin, illustrate a medieval interpretation of the Parable of the Wise and Foolish Virgins.

In the Gospel according to Matthew, Christ tells this story, in which the former embody readiness and the latter laxness. However, he does not mention the Tempter. On the portal of Strasbourg Cathedral, this demon lures the foolish virgins with his elegance, making them forget God, while Christ leads the wise virgins to heaven.

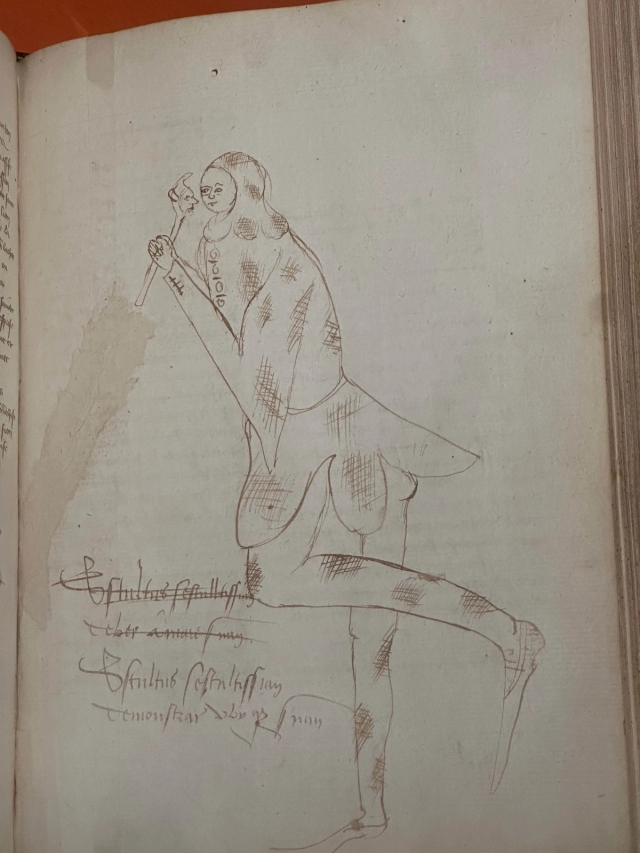

Anonymous artist

Fool addressing his bauble

The Recueil de mystères et de pièces relatives à plusieurs saints

France, about 1440

Pen and ink on paper

To make a portrait of his fool Triboulet, René of Anjou (1409-1480) called upon one of the great Italian sculptors working in his court: either Francesco Laurana, or his master, Pietro da Milano. From the marble block, the sculptor released an effigy bursting with life; the fool seems almost as glorious as a Roman emperor.

The subversive fool was so intrinsic to court society that he even became a character in its games: a chess piece and a figure on playing cards, particularly those of the tarot, which appeared in the 15th century in Europe; the first known examples are displayed here. In this form, he was the ancestor of the joker on our modern playing cards.

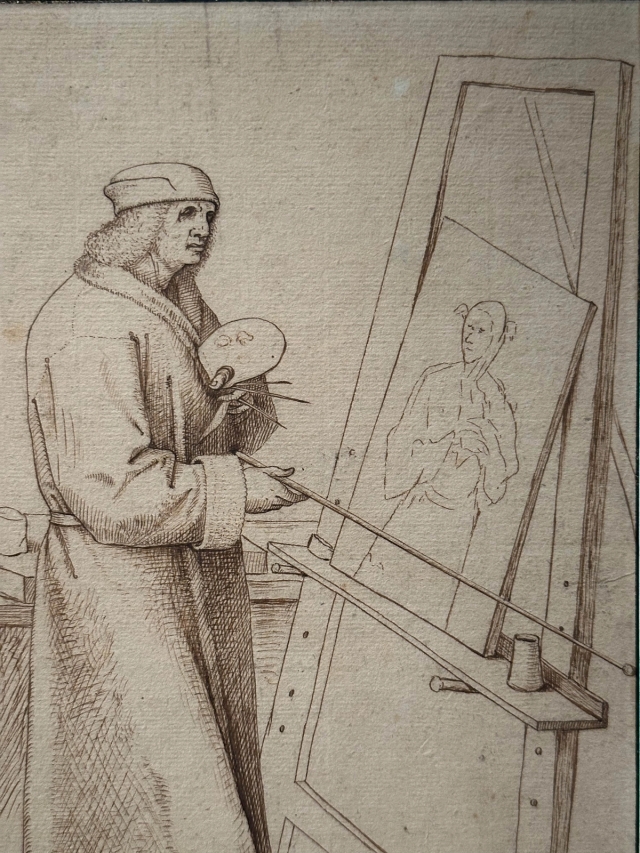

After Pieter Bruegel the Elder (about 1525-1569)

Painter at His Easel

Belgium or Netherlands, 16th century

Pen and brown ink

Hieronymus Bosch (about 1450-1516)

Oil on panel

The extraction of the stone of madness, an imaginary operation, was a very common subject in the 16th century. Here Bosch provides a very early and original version, substituting a flower for the stone - yet in the inscription, the patient is indeed asking the surgeon to remove a stone. Many elements of the painting, like the flower, have a sexual connotation, so the type of madness in question is probably related to lust.

Cornelis van Haarlem (1562-1638)

Portrait of the Fool Pieter Cornelisz van der Morsch

Late 16th century

Oil on panel

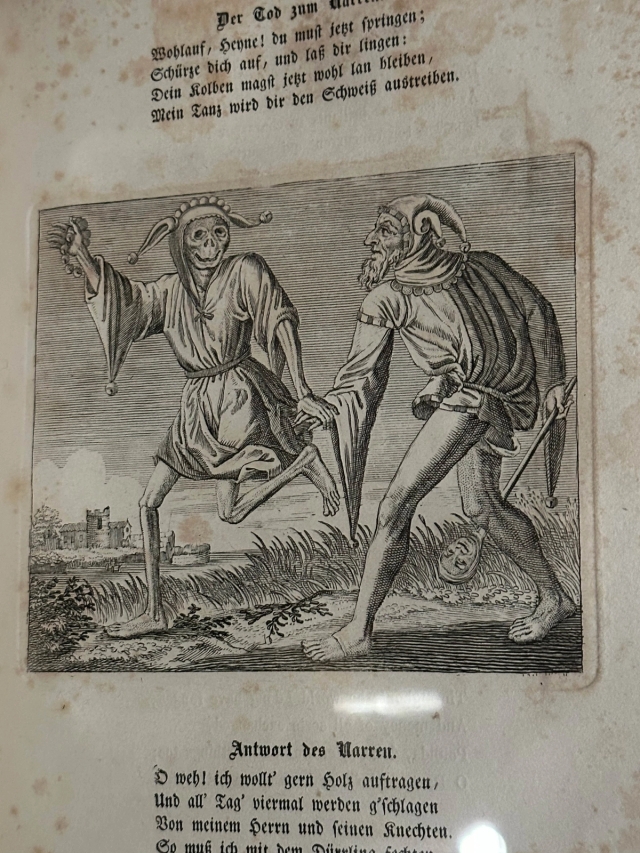

Anonymous artist, after Matthäus Merian (1593-1650

Death says to the fool:

Come Hal, dance now without a jest,

Gird up your loins and do your best;

Your club you may leave on the ground

My dance will sweat you, I'll be bound.

François-Auguste Biard (1799-1882)

The Exorcism of King Charles VI's Madness

Oil on canvas

Biard's interest in madness had already been manifested in The Lunatic Hospital (1833). At the Salon of 1839, he exhibited no fewer than six paintings, including The Exorcism of King Charles VI's Madness. In this work, the painter dramatises the scene by showing the king convulsed by a rite of exorcism and upheld by a woman, either his wife or mistress. The painting, in the Romantic style, exploits oppositions of light and shadow to accentuate the dramatic intensity.

Hans Sebald Beham (1500-1550)

Male and female fools

Here, Beham denounces the folly of love, in a total reversal of the conventions of the garden of love and the codes of gallantry. The vessel on which the female fool rests her hand is an allusion to the rounded belly of pregnancy or the uterus, and thus to sexual intercourse.

As for her companion, he holds a Narrenwurst, or fool's sausage, symbol of both his lewdness and his gluttony.

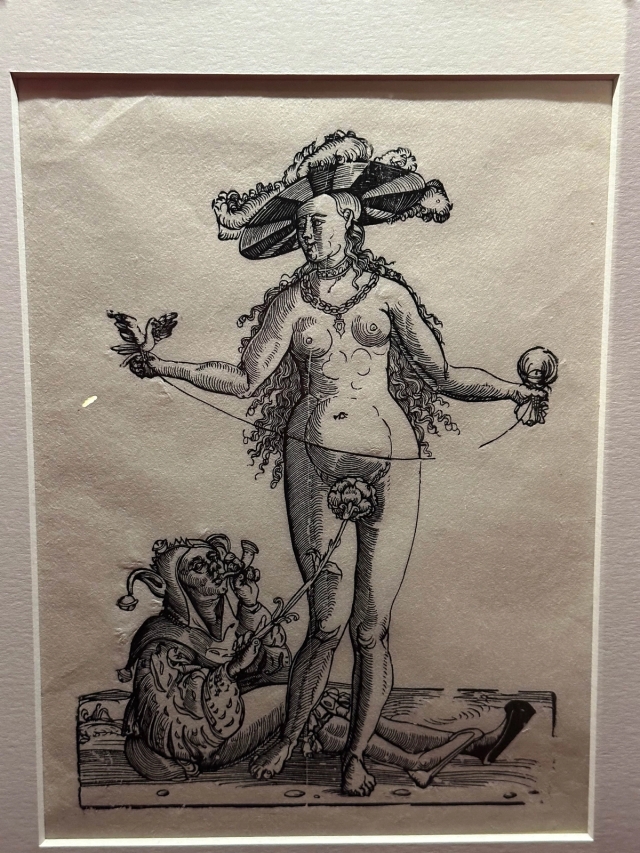

After Hans Sebald Beham (1500-1550)

Woman and Fool, or Pleasure, Woodcut

The woodcut shows a jester driven mad for love of a woman wearing nothing but the great feathered hat of a wealthy, elegant courtesan - doubtless an allegory of Pleasure, if not Venus herself. In one hand she holds a cuckoo, a 16th-century symbol for a man under the thumb of a courtesan. In the other she holds a baby's pacifier: the fool has returned to infancy under the spell of Pleasure.

Circle of Evrard d'Espinques (active between 1440 and 1494)

Tristan and Iseult drink the love potion

Illumination on parchment

The key episode of the story of Tristan and Iseult is illustrated in this collection of chivalric romances. Tristan, nephew of King Mark, goes to Ireland to find the king's wife-to-be, Iseult, and escort her back to Cornwall.

Tristan, being thirsty, drinks from a goblet - a fatal error, as it contains the love potion meant for Iseult and King Mark. When Iseult also drinks it, their fate is sealed: thenceforth, they are madly in love with each other.