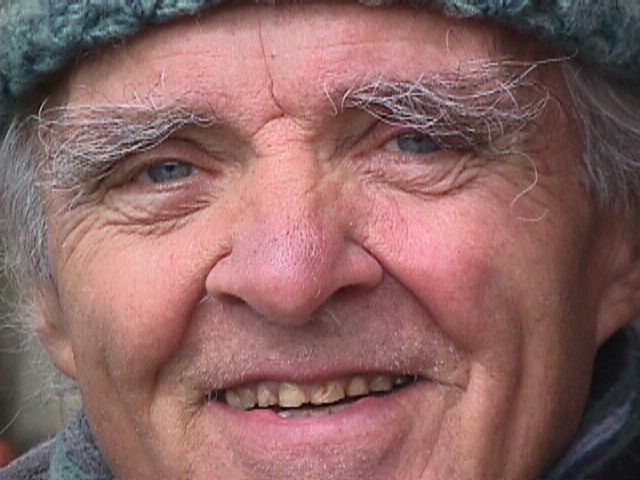

Conversation w/ Deva Manfredo

In June 2023, while working on commission in the Tuscan countryside I met Deva. Following is a transcript of the conversation we had, along with the picture I took of him and his work.

Well I’m not in the art scene anyway, I’ve always found it a bit snobby.

I didn’t care, I just did it for myself, and if there is an interest from outside it’s fine, but if there is no interest that’s fine as well. I never did it for money. My definition of art is very free. Since I was a child I have always designed and painted, around 6 I was already drawing. I’ve never had a professional relationship with the art world.

Do you still see art as a form of game, like a child playing?

Kind of yes. As a child, I was creating small landscapes with plants, and so on, where a lot of situations and narratives would unfold. A playful imitation of the world, you know? In many parts of my life, creating was also a necessity, often you compensate for something with creativity. Generally, suffering people create. It was a necessity for my growth, a healing force. And then it became a play which was for everybody.

Is there any kind of ideology you feel close to? I know you were part of Osho at some point.

Ideology, I would say, freedom with a responsibility for the community. It’s a very free situation at Osho you know? In the first years of the movement, Osho had the reputation of being a sex guru.

Which was true to some extent, wasn’t it?

Yes, yes, it was true. I don’t know the situation today because I’m a bit out of business for that (laugh). But for me, Osho was a school of life, with no real dogma. He’s not a god or something… I joined the community in Hamburg, Germany, as originally I wanted to study art at the academy there, but they didn’t allow me to enter.

Did you feel rejected by the official institution then?

Yes, a little bit. Osho was representing an alternative to the mainstream institutions, a form of counter-culture. Of course, we have never had any direct conflict with the official institutions, but it has never been approved by them. In other regions, however, there were conflicts (like in America - CF. «Wild Wild Country»). The controllers don’t like freedom, and in the US it became too provocative for the narrow-minded.

Was it also the case that it represented a threat to Capitalism?

No, not really. Osho wasn’t against money. The most important was living in the moment, without a profit-interest. In that sense, it was a different story. But the pressure mostly came from Christian fundamentalists, who were very strong in the US. But the idea was that if you liberate the individual you also liberate the society.

Do you see Art as a tool of counter-culture? How could we make Art counter-cultural again?

I would give more weight to creativity in everyday life. Everybody can do what they can with their possibilities. The more equal society is, the more possibilities there are. But of course without the Dogma. Living in the moment, that is the story, isn’t it? All of my ideas are always very spontaneous... Society wants to put you in a box, also my family tried to put me in the box. They wanted me to become a catholic priest, they sent me to a college of Franciscan monks for some years, they put me in Latin and Greek schools, and so on. But they never asked me if I wanted to be part of that. So I found my subversive way of escaping, and art was a very important part of that.

I see a lot of common things between being a priest, an artist, or a Shaman, it all requires faith.

Yes, sure, in the end for me it became all inter-winged also. And I mean, eventually, I ended up in some kind of religious community (Osho NDR). So I was not a catholic monk, but some other kind of monk (laughs).

Did you consider yourself a bit biggot at the time? Or proselyte? Would you preach when you were in Osho?

No, I conducted meditations, and eventually explained to people how meditation worked for me, but not in a proselytizing way.

Has working with those stones replaced meditation for you? It sounds like a very meditative practice.

I would say it’s a kind of meditation. I did for quite a few years those group meditations daily, which were very physical. But I don’t do this kind of body meditation anymore, the one that liberates blocked parts in your body. Because I don’t feel like I have anything blocked anymore, I feel very free. First I expressed my blockages in painting and then slowly freed myself. But there has always been a will to understand and work with reality. First, copy it, and then create your reality...

Developing your reality is interesting. In that sense, could making art lead to ideology? First, you put gestures, and then come the thoughts...

No, it leads to reality, not to ideology.

But isn’t reality always tainted by ideology?

Sure, normally yes. But Ideology is a mind concept. You develop a world sight, and you try to change the world so it becomes in line with your ideology. But I don’t think that’s the way it functions. I take the world, I take what I find and create a different reality, but not necessarily an ideology.

How much trial and error is there in your work?

Naturally, I look for the most perfect stone, the one that won’t require my intervention. But I mean all life is trial and error. I think the main characteristic of what I’m doing is that it’s very spontaneous, it’s not planned. It’s never a search of mind, it comes immediately or it doesn’t come, where there is a will, there is a way.

That’s coming back to the idea of religious faith, isn’t it?

Yes, it is.

Do you think people still have faith in changing the world? Do you see people much more resigned than in the ‘60s-70s?

I mean the dominant classes of society will always want to keep the status quo, that’s why they sabotage any changes and progress. It’s hard stuff, a lot more of egoism. Our society demands that, it creates more egoism, you always have to fight against each other, to compete. I’ve never wanted to be part of that, I’ve never been interested in competition, I wanted to do my own thing.

What do you think of art schools? The idea that art can be taught.

Art should be part of normal life, I often tell the school teachers who come here that every school should have a play-place, a bit like this park where we are now.

Like a creative play place? Institutionalizing a way to «manufacture freedom»?

Yes, every school should have a creative play place. But then come problems of insurance, bureaucracy, and so on. Freedom for people to express themselves playfully. But naturally, the more you are in a box, the more you express the box. I have a play place here in the forest, and when groups of children or students come and visit, they are always 100% into it. They need it, and very often the reality of life does not allow them to play, you know?

When did you develop the conscience that you would be happier «outside of the system»? Or in outsider communities. That the system was soul-crushing.

Already as a child. There was a sandbox in a small park behind the flat where we were living, I could play freely without the interference of others, including my parents. My mum was also a controlling person, but she did leave me spaces to play freely. And I think that was the beginning of what I do today. In a society, there is always a teacher who doesn’t like this or that and tells you not to do it. Or you would have a child from the playground who likes to destroy things. And in that sense, I developed this kind of underground attitude, you do your things, I do my thing. I mean everybody is different and has their biography, but you have so many crossroads on your way that if you go away from your own authentic will, you’ll take the wrong bifurcations, which could lead you into nowhere, or to aggressivity and so on, and you’ll then become a cop or a soldier. If one road is blocked you need to look for another road, which will lead you to an authentic being, made of love, freedom, and play.

When did you become more political?

I became more of a leftist when I saw the Pentagon papers of the Vietnam War. My father was a soldier, until 1945... He fought for Hitler. He was in the assault unit, they made those landing operations everywhere.

Do you think he believed in Hitler?

Well, naturally he was educated as a German nationalist. But he was not a fascist. He wanted to become a forest man, but after the First World War, there was no work in Germany. But the police had work, because of the repression of communists and fascists and the difficult political situation. So my father went to the police, and then he was enrolled by the Luftwaffe, the German airfare.

So did the system rope him in?

Yes, it did.